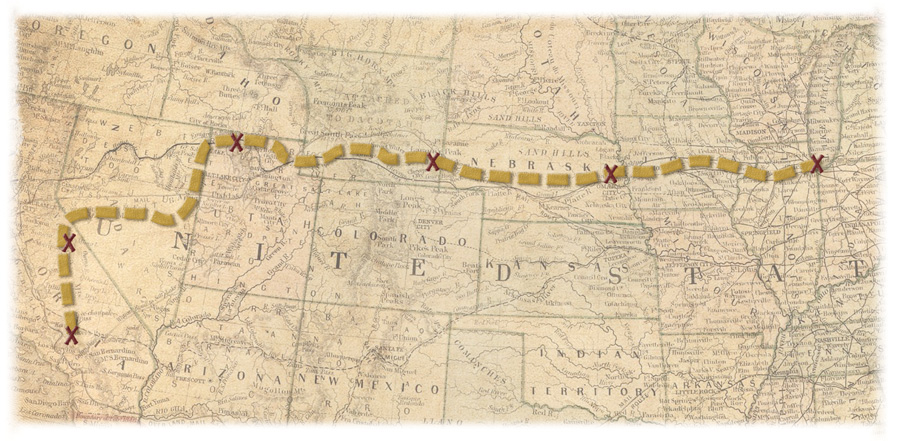

Imagine finding your way across a continent in an era that predated the Federal Highway System. It was a time when “roads” might refer to unmaintained dirt logging trails and where paved streets were few and far between. But the unknown horizon was part of the allure for Hotel del Coronado founder Hampton Story, who motored across America over a century ago, long before GPS, cell phones, directional signage and most maps.

In San Diego history circles, Hampton L. Story is best known as one of the founders of the famed Hotel del Coronado, which he and partner Elisha S. Babcock, Jr. established in 1888. Perhaps lesser known is the fact that Story, prior to relocating from Chicago to San Diego at the age of 53, had already made a name for himself with Story & Clark, a Chicago piano manufacturing company that boasted a national reputation.

Although Story’s tenure at The Del was short-lived (San Francisco entrepreneur John D. Spreckels soon assumed ownership of the resort), Story continued to oversee his interests in the Story & Clark piano company after relocating to the Los Angeles area. Never one to rest on his laurels nor let his adventurous spirit wane, Story then took on a new interest, as documented in his essay, “My First Trip Across the Continent by Motor Car” (1911); born in Vermont in 1835, Story was a vigorous 75 years young at the time.

On June 1, 1911, Story and travel companion John C. Loef set out from Pasadena to New York in a 1911 Packard touring car. From its first models in 1899, Packard was a leading luxury carmaker, carrying a reputation for high quality, reliable cars up to World War II. But Story’s sojourn was anything but luxurious. In an 11-page typed account, Story relates the preparation and provisions required, the intended route (sketchy at best), and the mishaps and majesty of a cross-country trip at a time when there were few roads to connect the West Coast to the Midwest.

Outfitted for Adventure

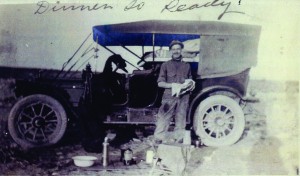

Equipped with canvas tenting and a “hair mattress,” along with food, water, and gasoline, Story and Loef were also prepared for the inevitable touring misadventures. Their extensive tool kit included a block and tackle pulley and lever system for lifting heavy objects, shovel, crowbar, ax, and mud hook. Establishing an actual itinerary, on the other hand, was all but impossible. Wrote Story, “We could find out little or nothing concerning the route we had chosen or the condition of the roads.”

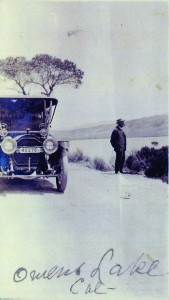

According to Story’s trip diary, the pair traveled directly north from Pasadena, camping the second night in the Owens Valley, an area that held Story in awe: “A portion of Death Valley could be seen in the California distance, with the mighty snow-capped peaks rising above us. Let me say right here: the scenery for the entire length of Owens Valley is not surpassed, even if equaled, in Europe or America.” This was just two years before Los Angeles, under the leadership of its water and power director William Mulholland, controversially won water rights to the Owens Valley, eventually turning its green valleys brown.

Nevada and Utah

The next day’s travel (crossing the California-Nevada border) proved to be “one of the longest, roughest and most difficult mountain grades of the entire trip … in many places [we] were obliged to clear the road of big boulders and other obstructions.” In trying to scale one “seemingly nearly perpendicular hill about 150 feet high,” the steep grade prevented the gasoline from flowing down into the carburetor, so Story and Loef were forced to inch up the incline backward, “blocking the wheels and clearing out the boulders” as they worked their way to the summit.

The men then traversed Nevada in a mostly northeasterly direction, heading toward the upper border of Utah — at one point racing with bands of wild horses. The northernmost stretch of Nevada proved especially difficult: “We could not find out whether there were passable roads … or not.” Asking directions sometimes proved fruitful, but just as often “no one could give us any information about the way to get through.” So, “with compass in hand,” Story and Loef tried various dirt trails, many unsuccessfully. After one particularly exasperating day, the men had traveled 150 miles “though much of this distance was decidedly indirect.”

The next day was just as demanding: “We encountered boulder-strewn hills with little sign of a traveled road.” At one point, Story and Loef had to cross “alkali flats and water courses with no bottom in sight.” Accordingly, the men “bridged several of these with thick layers of sagebrush and [we] would rush the machine across them before it had time to sink.”

Northern Utah, however, surpassed their expectations, with “an excellent thoroughfare,” as Story described: “The Mormons had entered and developed this region. Fine farms and thriving villages were encountered all the way to Ogden. This was a great surprise to us for it was unexpected.”

Wyoming and Nebraska

Traveling into southern Wyoming was more challenging when a blizzard at an elevation of 10,000 feet made it difficult to light a fire for breakfast and the men were forced to put chains on their tires. The chains were also required a couple of days later — this time to navigate a stretch of deep “bottomless” sand. Once again, the route was uncertain:

“Several blind untraveled roads confronted us. Selecting one, we went on several miles, when it abruptly ended,” Story wrote. “It was a woodcutter’s road. Back we came and tried another with the same result. The third time we took a very blind trail. This at last led us out onto a traveled road to Laramie.”

Continuing almost due east across the center of Nebraska produced more of the same: “We got lost several times and went many miles out of our way. We encountered no signboards and no inhabitants, and it was mostly guesswork. Diverging roads were frequent.” But as the men approached the Iowa border, their luck improved:

“We soon got into a well-traveled, excellent road, passing through a rich farming country, a pleasant and agreeable change from the long desert trip. This day we made 226 miles, the longest and most comfortable of any day’s drive so far, arriving at Omaha the following day.”

At this point, the gentlemen travelers shipped their outdoor camping gear back to Pasadena as they prepared for the remainder of their travels along more established roadways.

19 days later, arrival in Chicago

From Omaha, Story and Loef spent a night in Des Moines, followed by another night in Iowa City, before crossing the Mississippi River on a bridge, arriving in Chicago 19 days after leaving Pasadena.

This is where Story concluded his diary … but not his cross-country adventure, continuing on by car to New York, “thereby completing the ocean-to-ocean trip.”

Two years later, Story and Loef made a second transcontinental crossing

taking a southern route, roughly following the Santa Fe Trail from Pasadena to Chicago. This time their travels took them through Arizona, New Mexico, southern Colorado, Kansas and Missouri. Hampton L. Story died in Los Angeles in 1925 at the age of 90.

Postscript: According to the Federal Highway Administration, in 1913, the Lincoln Highway Association was formed to address the need for a paved east-west highway. The group, named in honor of President Lincoln, elected the president of the Packard Motor Car Co. as head of the organization. At the time, there were no quality long-distance roads in the United States. The fledgling organization raised an initial $4 million in order to begin the building of a coast-to-coast highway. A primary model section was built south of Chicago, which successfully brought awareness to the public about the need for better roads. President Woodrow Wilson brought further attention and support to the effort when he explained that it “threads various parts of the country together.” The Lincoln Highway is now known as U.S. Route 30.

Christine Donovan is director of Heritage Programs for Hotel del Coronado, where she has authored six books on the hotel’s history. Information and photos for this article were provided by Hampton L. Story’s great grandson, Peter Story.

Hampton L. Story surveys Owens Lake in California. According to his trip diary, the Packard was outfitted with oversized tires, including two spares and, “On reaching Chicago, two of the tires still had California air in them.”

Hampton L. Story surveys Owens Lake in California. According to his trip diary, the Packard was outfitted with oversized tires, including two spares and, “On reaching Chicago, two of the tires still had California air in them.”

Story’s driver and travel companion, John Loef, poses with his makeshift kitchen. The 1911 cross-country trip was physically demanding, and Story’s appetite increased proportionately (“Reminded me of my boyhood days,” he wrote in his diary.) Along the way, the men prepared hearty breakfasts of ham, eggs, pancakes and coffee, as well as campsite dinners.

Story’s driver and travel companion, John Loef, poses with his makeshift kitchen. The 1911 cross-country trip was physically demanding, and Story’s appetite increased proportionately (“Reminded me of my boyhood days,” he wrote in his diary.) Along the way, the men prepared hearty breakfasts of ham, eggs, pancakes and coffee, as well as campsite dinners.

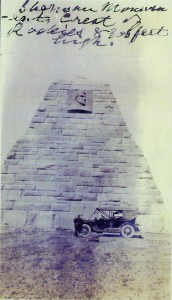

Erected by the Union Pacific Railroad Co. in 1882, the 60-foot Ames Monument in Sherman, Wyo., once marked the highest elevation of the transcontinental railroad (8,247 feet). In 1901, the railroad moved the line, but the monument – designed by eminent architect Henry Hobson Richardson and featuring medallions by acclaimed American sculptor August Saint-Gaudens – remained.

Erected by the Union Pacific Railroad Co. in 1882, the 60-foot Ames Monument in Sherman, Wyo., once marked the highest elevation of the transcontinental railroad (8,247 feet). In 1901, the railroad moved the line, but the monument – designed by eminent architect Henry Hobson Richardson and featuring medallions by acclaimed American sculptor August Saint-Gaudens – remained.