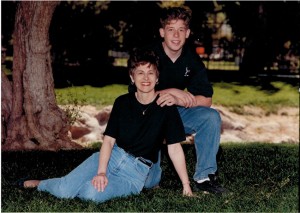

When her son Daniel, a California Army National Guardsman, returned home from his second tour in Iraq in 2008, Coronado resident Jean Somers wasn’t fully aware of his struggles to return to normal life in America. “He was living in Arizona, and since months would pass between visits, we weren’t aware of the dramatic changes in him. And his voice could cover up his problems over the phone,” Somers said.

What Somers wasn’t able to detect was that her son was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), an anxiety disorder common among military personnel who have witnessed combat (and people who have experienced a life-threatening trauma; women being more at risk than men to develop the disorder). According to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), 11 to 20 percent of Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom veterans are diagnosed with PTSD in a given year.

“It’s such a prevalent problem,” said Somers. “A veteran’s life is so effected after military service, but they tend not to want to talk about it. A big part of getting better is admitting there’s a problem, but there’s a stigma about owning up to what it is — a problem with brain function.”

Somers explained that many veterans hope to get into service careers such as the police force, but disclosing issues with mental health can put those aspirations at risk. “The chances of a post-military career like that are poor once a veteran has discussed a struggle with mental health — so they just don’t talk about it,” she said.

Somers explained that many veterans hope to get into service careers such as the police force, but disclosing issues with mental health can put those aspirations at risk. “The chances of a post-military career like that are poor once a veteran has discussed a struggle with mental health — so they just don’t talk about it,” she said.

Dr. Sonya Norman, research psychologist at UC San Diego and the San Diego Veterans Association and director of the PTSD consultation program for the National Center for PTSD, concurred: “Many returning veterans equate admitting help with weakness. Others are just really busy trying to pick up where they left off with their young families and normal lives. Or, they think their struggles are just part of an adjustment process and it will get better. But sometimes it doesn’t. People shouldn’t have to hit bottom to seek help.”

All too often, however, many do hit bottom before receiving the support they need. The VA reported that an average of 22 veterans commit suicide every day.

“Daniel left us a detailed note justifying his suicide,” said Somers. Her son took his life in June 2013. “It’s awful that he did it. We just didn’t know he was having so much trouble.”

Dr. Eileen Callahan, a clinical psychologist who runs a private practice in Coronado specializing in PTSD, explained how many returning service members have difficulty coping. “There are three categories of PTSD symptoms. The first is the ‘re-experiencing,’ which includes things such as nightmares, re-living of a traumatic situation and intrusive thoughts and memories. The second category is ‘increased arousal,’ which includes heightened awareness of the surrounding environment, increased irritability or anger, and easy startle responses. The third is ‘avoidance’ symptoms, which involve avoiding talking about, remembering, or allowing oneself to feel the impact of a trauma.” It is also common for people to avoid going places where there may be a crowd, loud noise or anything that may remind them of the trauma. It’s these avoidance behaviors, she explained, that can exacerbate PTSD and make healing more difficult.

Callahan advised that if you notice a loved one significantly withdrawing from life or displaying any of the symptoms listed above, encourage them to seek help. “These symptoms do not mean the person is ‘going crazy,’ a concern I’ve often heard expressed. Seeking help, the sooner the better, will help a person heal and recover from the impact of trauma.”

Coronado marriage and family therapist Lilach Harris noted, “Many returning veterans feel kind of lost. You go through trauma, you change.”

Harris grew up in Israel, where military service is required of all Israeli citizens, women included.

“I know war from a different angle,” she said. “I grew up in a country where everybody is a soldier.”

Here in the United States, Harris has experience working with the military and the Wounded Warrior Project — so she’s no stranger to veterans struggling with PTSD. Today, she sees clients from all over the county at her office on the third floor of the Coronado Plaza building on Orange Avenue.

Although her clientele demographic in Coronado includes teenagers, families, and couples, with three military bases in the area it’s not surprising 75 percent of the patients Harris sees are service members.

Harris incorporates Eye Movement Reprocessing and Desensitization (EMDR), which allows individuals to process traumatic memories using various eye movements in conjunction with cognitive therapies. Harris points out that EMDR is not for everyone, and that individuals “have to be in a good place.” Conditions such as substance abuse or feelings of dissociation from reality make some patients ineligible, she noted, as their situation could potentially worsen. When used properly however, EMDR can be extremely useful, Harris said.

Harris noted that it’s important for those who live with someone with PTSD, “not to be judgmental … To not focus on who the person used to be, but who they are now.” Additionally, Harris explained that it’s natural for returning veterans to feel like their sacrifices aren’t appreciated. “In the event that a friend or family member with PTSD wants to talk about what they’re experiencing, often the best thing to do is just listen.”

Norman added, “It’s normal to want to help but feel you don’t have the right thing to say. Just be encouraging.”

Norman also advised those supporting someone with PTSD to “take care of yourself. It can be incredibly stressful to care for someone struggling and it’s easy to get pulled into it. When your loved one is isolated, it’s easy to become isolated and lonely along with them.”

The feeling of marginalization many PTSD sufferers experience means they are often strong advocates for others with their condition. Norman pointed to several effective programs started by the VA. One is called “Coaching into Care,” which coaches friends and family of someone with PTSD on how to help. At the Veterans Center for Mental Health Services in Point Loma, veterans can sit down and spend time with other veterans, talking about their experiences and struggles. Another helpful program, “AboutFace,” pulls together veterans of all ages, genders, and ethnicities with PTSD to share what they’ve gone through. “A lot of veterans just need that ‘buddy’ to relate to and get help from. These programs are that buddy,” said Norman.

After Somers lost her son, she and her husband, Howard, began Operation Engage America (OEA), which hosts a seminar every June in San Diego to raise awareness about PTSD and how to support loved ones who are suffering. “We have made it our mission to address the multiple barriers that kept Daniel from receiving the proper treatment he so desperately needed. In that process we hope to ensure that no other veteran or family suffers as ours has,” said Somers. For details about the OEA seminar this June, visit operation-engage-america.org.

Harris said the most rewarding experiences are when she is able to see her clients make progress, or hear a military spouse tell her how much their partner has improved. And while the person with PTSD will likely never be the same person they were before the trauma, it is very possible for an individual to integrate their experiences into their everyday life in a way that is not so distressing to them or their family members.

“You don’t have to suffer in silence,” Harris said. “Focus on the moment. Focus on the future.”

Norman had similar words of encouragement: “You can recover. You can get effective treatment and live a fulfilling life you feel good about.”