In the shadow of new high and mid-rise luxury condominiums in Bankers Hill sits a historic apartment complex of classic lines, designed by two of San Diego’s most revered architects of the era, Frank Mead and Richard Requa.

The Palomar Apartments, which dovetailed with the building of the 1915 Panama-California Exposition in Balboa Park, is now a San Diego Historical Landmark, with the plaque bearing the dates of 1913-1915, denoting the years of its construction.

Coronado resident Mark Warner has just completed a three-year restoration of the apartment complex, which he bought in 1989, that included among its earliest residents two of San Diego’s most famous personages, Charles Lindbergh and Wallis Warfield Simpson.

One of the few surviving apartment buildings of a century ago, the Palomar today sits in the shadow of cranes that carry construction materials high into the air for condominiums under construction in the popular Bankers Hill area.

While nearby luxury developments feature floor-to-ceiling windows, the Palomar maintains an unassuming exterior facade. But once inside, the development opens to a charming atrium, with the original ceiling constructed of safety glass, a novel design element for the period, that floods the interior with light. An intimate European village atmosphere unites the 25 apartments that open onto the garden courtyard from its three floors.

Warner’s renovation included all the electrical wiring, plumbing, roofs, exterior and interior painting and upgrades. He still has all the original furnishings in storage. “Another project for another day,” he quipped.

The building elevator is an Otis. Warner had to replace the motor and switchboard in 1995, but the cage is still original. “I would guess that 75 percent of it is original. At the time of its ‘demise,’ I was told by Otis that it was the third-oldest operating elevator in the world. The Hotel Del was No. 2.”

Former Coronado resident Christen Simeral, a web and social media editor for Fox 5 news, rents a studio at the Palomar.

“I love the character of this place,” she said. “It feels like you are transported to another time. You just don’t see places like this too much anymore.”

Simeral points to her kitchen’s “funky” black and yellow tile, all-wood doors with glass knobs and crown molding as historical touches that define the property as something special. “When friends come over they always comment on how charming it is here,” she said.

She also loves Bankers Hill and its burgeoning restaurant scene, with personal favorites being Cucina Urbana and Barrio Star, both within walking distance on Fifth. “Balboa Park is right across the street, which is perfect if you’re a runner like me. And there are free yoga classes there on Sundays.”

The apartments feature a unique blend of African Moorish, Spanish and Craftsman-style architecture, reflecting the influences of the Mead & Requa architectural firm, which was founded in 1912.

Born in New Jersey in 1865, Mead was initially influenced by North African architecture due in part to a visit he made to North Africa to photograph the Bedouin villages of the Sahara. Moorish influences are found throughout the Palomar’s interior, including arches surrounding the atrium, “keyhole” shaped doorways, Spanish roof tile, tile and wood detailing around windows, wrought iron balustrades and original geometric design ornamentation on doorways and arches.

Requa, born in Illinois in 1881, became an apprentice with Irving Gill in 1907, despite the fact that he lacked any formal training as an architect.

He was later the lead architect for Balboa Park’s second big event, the 1935 California Pacific International Exposition, intended to promote the city and remedy San Diego’s Great Depression ills. Requa oversaw the design and construction of many new buildings, including the International Cottages and the Spanish Village.

In his book, The Duchess of Windsor, author Charles Higham states that Wallis Simpson lived in Apartment 104 of the Palomar. At the time of Simpson’s residence in the 1920s, the view from 104 included Balboa Park, which still had many signs of the 1915 Exposition.

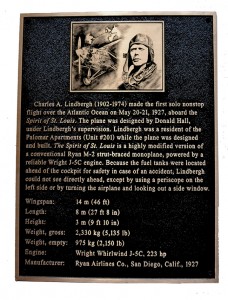

Aviator Col. Charles Lindbergh stayed in the Palomar before embarking upon his famed trip across the Atlantic in The Spirit of St. Louis on May 10, 1927, the first leg of which departed from San Diego. He is said to have stayed in Apartment 201.

As part of the restoration, Warner commissioned a one-sixth-scale replica of Lindbergh’s plane; it is suspended high in the building’s atrium, just below the glassed-in ceiling.

The complex includes nine studios and 13 one-bedroom units with enviable rents of $975 to $1,750. There is also one two-bedroom, one junior penthouse and penthouse, the latter designed by Requa as an open-air teahouse. It has since been enclosed. Another Requa design motif is the building tower that soars above the rooftop patio; it holds the operating mechanics and cables for the elevator. Warner has outfitted the rooftop patio with comfortable patio furniture and it is a popular common area for tenants.

While gated and secure and with a laundry room on the premises, the complex does not include parking. Simeral solved that problem with a $100-a-month parking pass at the “Mr. A’s” commercial building at Fifth and Maple. (The Palomar is a block away at 525 Maple St.)

Warner can’t help but be amused by what he attributes to good luck in owning the apartments where he once served as the resident manager. In fact, he looks back on his life as a series of fortuitous events.

From the time he was 13 years old, Warner said he knew he wanted to go into real estate.

“I started reading Forbes and Business Week when I was nine years old. Back then, I saw that all the rich guys made their fortunes in real estate — this was before there was such a thing as high tech.”

Those magazines were a staple around the Warner house, where Warner’s father worked for Bethlehem Steel, handling public relations for the company. The family lived in Los Angeles, then moved to Bethlehem, Penn., the firm’s headquarters, then back to Los Angeles, when his father switched to the banking industry. Young Mark had the good fortune to attend one of the best private schools in the nation, Chaminade College Preparatory in Chatsworth. But entry into the school was somewhat touch-and-go.

“The dean was sort of ho-hum about me and my academic record,” Warner recalled. “But then he asked if I had played any sports in Pennsylvania. “Football,” I said. “State finalists, 11-1 for the year.”

He was in… and directed to check in immediately with the football coach.

During his teenage years, Warner and several friends made a trip to Tijuana and on their way back, spied the University of California at San Diego sitting high on hills above the Pacific Ocean. “That was the one and only school where I applied,” he said.

Or so he thought. He was accepted as a business major and drove down to visit his new alma mater, but discovered he had applied and been accepted to the University of San Diego, not UCSD.

“I asked, ‘Where’s the ocean?’” and the provost pointed to the far, far distant horizon.

Warner may poke fun at himself, but realizes that he chose the right school: At the time of his application, UCSD didn’t even have a business school and today the University of San Diego is top ranked among business schools, and its Burnham School of Real Estate receives even higher honors.

Warner graduated from USD on a Saturday in 1980 and the following Monday reported to work at the real estate brokerage firm of Cotton-Ritchie. In 1982 he became resident manager, living in the penthouse at the Palomar, one of Cotton-Ritchie’s clients. He was the broker of record for the building’s sale in 1986 and bought the building in 1989. “I lived above the store until 1998,” he said. That’s when Warner bought a home in Coronado, having become acquainted with the town through the late Lorton Mitchell and Hector Esquer and other friends with whom he played baseball and went fishing. Today Mark and Ramona Warner, who married in 1999, have two children, Johanna, 15, and Jake, 12. “The Palomar Apartments,” Warner said, “is my kids’ inheritance.”

Each time a new high rise goes up near the Palomar, Warner just smiles. “I always call to see what the rental rates are; they usually range about 50 percent more.”

But you can’t put a price on history.