When the printing press was invented in 1440, there was a widespread panic over how the new technology would affect humans and their interactions with one another. Coronado psychologist Dr. Roderick Hall explained, “People were afraid that with the new accessibility of books that everyone would simply give up on their daily lives and do nothing but read all day.”

Fast forward more than 500 years, and we find ourselves again in the midst of a torrent of technological advancements — and a lot of questions about how these new technologies are changing the way we think, behave, and interact with the world around us.

Coronado psychologist Dr. Jada Cade explained that because of their relatively recent advent, the effects of the Internet and technology on the brain still aren’t fully known — and there is a lot of controversy around the research. One thing is apparent, though: “Research says the more we continue habits — the more frequently we engage in behaviors — the more our brains change. We can create neural highways based on our activity, and in my qualitative experience I’ve seen a lot of pitfalls in the overuse of technology.”

Cade explained that when someone becomes dependent on technology — the Internet, social media, texting, gaming, emailing — the constantly reinforced behavior tells their brain to no longer follow the original circuit of their neural pathways. “Our brains are already circuited for delayed gratification, tolerance for frustration and the ability to identify our emotions and reactions. But the instant gratification of modern-day technologies helps us avoid those processes, and the physiology of our brains is changed so that we are less adept at doing those things,” Cade said.

Dr. George Koob, a former neurobiology professor at the Scripps Institute who now serves as director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism at the National Institutes of Health, explained that studies indicate brains of compulsive Internet users show similar activity to brains of people addicted to drugs and alcohol, such as decreases in executive function (the ability to plan, process and control impulses), that make us feel reward (in other words, it takes more of the compulsive behavior for our brain to process the feelings of satisfaction we get from it).

Just as is the case with books that seemed so new and scary half a millennium ago, technology can be as helpful as it can be damaging, depending on how it’s used. In his practice, Hall has seen patients so involved with certain technologies, such as video games or virtual worlds like Second Life or Minecraft, that it saved their lives. “I’ve seen these games give depressed or suicidal people a reason to get up in the morning,” he said. He’s also seen other positive aspects to the activity of building these virtual worlds: many scenarios force players to be very industrious, searching for food and shelter in a “survival-mode,” or very creative, building and designing entire cities with infrastructure and parks.

Social media can also be a way for people to deepen relationships — relatives who live far apart can stay connected, information and knowledge can be shared quickly among like-minded people, friends can stay in touch after the school or work day. And with the Internet, users have endless information at their fingertips — the instant ability to learn, explore, and communicate.

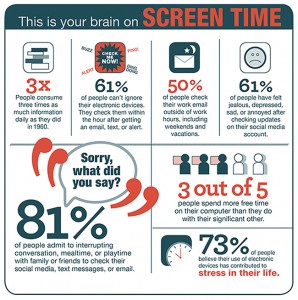

But many technologies are a double-edged sword. Communicating through a screen diminishes the quality of human interaction. “There are a lot of dangers in communicating when you aren’t face-to-face. Interacting with others from behind a screen disconnects you from them,” said Hall. “On the one hand, it’s easier to be mean to others when you’re not looking at their facial expressions, but you can also cause conflict unintentionally if someone misinterprets what you’re saying when they can’t see your facial expressions.”

Hall said that the Internet has also raised expectations for rapid response time. “We’ve grown to expect immediate responses — whether via text messages, emails, or comments and ‘likes’ on social media posts. And when people — especially children — don’t get that immediate response, they feel that others aren’t paying attention. They feel invalidated.”

Cade explained another troubling element of social media use: “Today’s adolescents are learning to identify their feelings based on social media feedback. They don’t know if what they are saying or doing is good or bad until they get online approval.”

In line with Koob’s argument, Hall expressed that among his patients (who are about 70 percent children and adolescents who’ve grown up in a digital world) he’s seen a decrease in higher-order thinking skills such as problem solving, processing information, and the ability to focus. “The executive functioning just isn’t there,” he said. “In addition to ‘helicopter parents’ not letting their children make mistakes and learn to solve problems, kids get immediate gratification from the speed of the technology at their fingertips. They don’t have to plan ahead to do research at the library for a homework assignment, and they don’t have to expend a lot of effort pulling together and sifting through information from multiple sources.”

A number of studies corroborate Hall’s observations, showing that with excessive Internet and/or online gaming activity, there is a loss of tissue volume in gray matter areas of the brain (where information processing occurs). Loss of this type of brain matter affects the frontal lobe, which governs executive functions. One study out of China showed that heavy Internet use causes damage to an area in the brain known as the insula, which is involved in our capacity to develop empathy and compassion for others and our ability to integrate physical signals with emotion — skills that dictate the depth and quality of personal relationships.

A study published in 2014 by the University of California, Los Angeles gave sixth-grade students a baseline test asking them to identify another person’s emotions using muted video clips. Half the students were then sent to a camp with no digital access but rather traditional camp activities such as hiking, archery and learning about nature. The other half worked as a control group, going about their normal activities with regular access to digital media (which for this group of students was about four and a half hours in a typical school day). After five days, both camps were re-tested: the group that went away to camp showed significant improvement in their ability to recognize emotions. The good news here? It only took five days away from electronics to improve their social skills and reconnect meaningfully with their peers.

Cade said that the brain can be retrained. “Of course, decreasing screen time can’t hurt. But it’s really about actively working to combat its effects. Engaging in deliberate self-talk — before you act or react, ask yourself how you feel, what are the effects of your behavior — retrains your brain’s neural pathways to work through those processes so you don’t lose the skill.” She added that practicing the reactions that happen naturally when not in front of a screen — noticing physiological responses, considering long-term impact of words and actions — can help users avoid some of the dangers of Internet interactions.

And Koob explained that preventing compulsive behavior involving the Internet is similar to how to prevent engagement in substances of abuse. According to Koob, access should be limited to pleasurable activity on the Internet much like one would limit one’s alcohol intake, and that adequate sleep, exercise and diet prevent the vulnerability to engage in compulsive behavior. “In short,” he said, “one has to self-regulate in the Internet domain much like one has to self-regulate other domains that involve powerful dopamine rewards.”

Like books, Hall said, computers have the potential to be positive, educational, enlightening and thought-provoking. “But,” he warned, “people tend to think of computers and smart phones as human and treat them as such and they’re not. It’s the human bond — not technology — that keeps society moving forward.”