As historian for Hotel del Coronado, which opened in 1888, I have become intrigued by America’s Gilded Age, the post-Civil War period when our nation’s industrial revolution generated unimaginable levels of personal wealth. It was this moneyed segment of society who became The Del’s first guests, many of whom lived off inherited assets. These were members of a privileged class, easily able to afford the expense of packing up their families and servants, making the trek from the colder climes of the East, and whiling away the winter in The Del’s turn-of-the-century luxury.

Quite a few of these guests hailed from New York, a stronghold of Gilded Age opulence. As Greg King writes in his book, A Season of Splendor, “New York was the only American city whose influence could be said to rival that of London, Berlin, or Paris. New York claimed the greatest wealth, the largest mansions … the most extravagant entertainments … and the most prominent citizens.” For many of America’s elite, this golden era extended into the 20th century, until the introduction of income tax (1913) and World War I (1917-18) exerted financial and societal influences from which even some of the wealthiest could not rebound.

My interest in the luxurious lifestyle of The Del’s long-ago guests was further piqued by Tony Perrottet’s New York Times article, “Regilding the Gilded Age in New York” (Feb. 27, 2015), which included a roundup of city sights that still evoke this golden past (a link to Perrottet’s article is provided at lifestylemags.com). With the article to guide me, I decided to fashion my own turn-of-the-century getaway in the Big Apple. Accompanied by my husband, Mike, and our good friends, who live in New Jersey, we spent two days trailing in the footsteps of some of New York’s most fashionable Gilded Age residents — traveling like the Vanderbilts, dining like the J. P. Morgans and luxuriating like Edith Wharton.

First stop: New York’s Grand Central Terminal (if you can arrive in New York by train, all the better). Originally built in 1871 by “Commodore” Cornelius Vanderbilt (so titled because of his extensive steamship holdings), the rail station was renovated a number of times before the present building debuted in 1913 after 10 years of construction. Excavation — to a depth of 30 feet below grade — accounted for most of the time lapse, during which the former terminal still functioned before being razed in 1910 and a temporary station called into service. Today, the Beaux Arts-style building (completely restored in the 1990s) is not only beautiful, it’s busy. With 500,000 visitors daily, it’s a landmark destination in its own right, boasting dozens of eateries and shops.

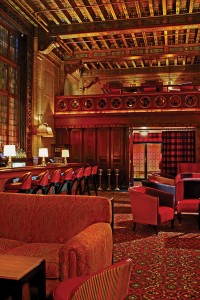

The Campbell Apartment is a not-to-be-missed hideaway within Grand Central Terminal. A former pied á terre and private office for 1920s tycoon John W. Campbell, it has been reconfigured as a chic cocktail lounge. Designed in the style of a 13th-century Florentine palace, the 3,500-square-foot space was meticulously restored in 1999. It’s a sumptuous setting to indulge in such period-inspired concoctions as “Prohibition Punch” and “Flapper’s Delight,” as well as scrumptious culinary accompaniments. Travel tip: Since it’s sometimes booked for private events, call ahead to confirm availability, (212) 953-0409. It also might be best to avoid weekday commuter hours. Although The Campbell Apartment is easily accessible from outside the terminal (via the pedestrian-only portion of Vanderbilt Avenue between 42nd and 43rd streets) as well as from inside the terminal, the signage is understated, so be prepared to ask for directions.

From The Campbell Apartment, we proceeded to historic Gramercy, still one of New York’s most fashionable neighborhoods (think Julia Roberts and Jimmy Fallon) and a throwback to long-ago glory, with its own private two-acre fenced park accessible to nearby residents who pay an annual fee for key privileges. Once home to the crème de la crème of New York society, Gramercy still boasts the fabled Players’ Club, a private social club that dates to 1888 and claims writer Mark Twain, famed Shakespearean actor Edwin Booth, and Civil War general William Tecumseh Sherman among its founding members. (The club and Gramercy Park are also charmingly featured in Woody Allen’s 1993 film Manhattan Murder Mystery, in which Diane Keaton’s character gushes, “That park is so beautiful.”)

Our home-away-from-home in Gramercy was The Inn at Irving Place, a boutique hotel housed in adjacent 19th-century Greek Revival townhouses at 56 Irving Place (with no telltale exterior sign to detract from its residential ambience). In addition to charming first-floor seating areas, the three-story inn features 12 antique-furnished guestrooms, each named to honor the life of Gramercy resident, Elsie de Wolfe, who started her career as an actress before seguing into interior design and publishing the definitive classic The House in Good Taste (1913). De Wolfe socialized with a wide variety of notables, and our spacious guestroom was named for fellow actress Sarah Bernhardt. As a young woman, de Wolfe was presented at Queen Victoria’s court in 1883, and after her marriage to British diplomat, Sir Charles Mendl, de Wolfe became known as Lady Mendl, for whom the inn’s tearoom is named.

On our second day in New York, we enjoyed coffee in the childhood home of Edith Wharton (today a Starbucks … but the exterior upper stories are intact); check it out at 14 West 23rd St. Born into wealth and an impeccable social lineage, Wharton (1862-1937) portrayed 19th-century upper-class New York society in her novels, while she lived the life of Gilded Age affluence. It is said her parents — George Frederic and Lucretia Stevens Jones — were the couple for whom the expression “keeping up with the Joneses” was coined.

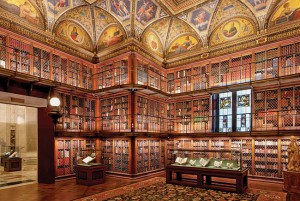

Afterward, it was off to the Morgan Library and Museum, the highlight of our Gilded Era tour. John Pierpont Morgan (1837-1913), the son of a banker, became one of America’s premier financiers and industrialists, helping to fund and consolidate companies such as International Harvester, United States Steel, and General Electric. In 1906, adjacent to his home, Morgan built a library at 225 Madison Ave. to house his private collection of rare books, manuscripts, and artwork, including three Gutenberg Bibles. After Morgan’s death in 1924, his son dedicated his father’s buildings, along with 14,000 rare books, as a public institution (a later addition connected the two structures). Today, the museum includes the Morgans’ library and private office (with his original desk and furnishings). Offering tours daily (themorgan.org for details), the library and museum also feature an expansive and well-curated gift shop, café, and upscale restaurant (located in the original Morgan family dining room; reservations recommended).

Later that day, back in Gramercy, we located the homes of famous former residents, many of whom are notable American authors. O. Henry, who roomed across the street from the inn, is said to have frequented Pete’s Tavern, just down the block and one of the city’s oldest restaurants/bars (est. 1864), where the author reportedly penned his classic The Gift of the Magi (1905). Kitty-corner from the inn is Elsie de Wolfe’s former residence (49 Irving Place), a three-story, brick row house, looking much the way it did when she lived there and is still privately owned (some claim an earlier resident was Washington Irving, who wrote Rip Van Winkle and for whom the street is named). Playwright Oscar Wilde once lodged at 47 Irving Place. For an architectural treat, we sauntered down to 19th Street, between Irving Place and 3rd Avenue, to view New York City’s “block beautiful,” filled with 19th-century brownstones, some with carriage doors still intact. In a nearby neighborhood is President Theodore Roosevelt’s birthplace and a reconstructed version of his original boyhood home, where he lived from 1858 to 1872.

For dinner, we joined the smart set at Delmonico’s, heralded as New York’s oldest restaurant. Although the eatery has enjoyed a variety of permutations, in a number of locations with a roster of different owners, this is the most enduring version, opened in the mid-1800s at 56 Beaver St. (its alternate address is 2 S. William St.). Restaurants were a rarity in the mid-19th century, and Delmonico’s was at the forefront, credited with establishing á la carte pricing and introducing such culinary classics as “Delmonico steak” (a specific cut of beef) and “Delmonico potatoes” (mashed potatoes topped with grated cheese and breadcrumbs). Today, Delmonico’s is also known for its lobster Newberg (served in shell), along with an amazing array of delicious side dishes and desserts.

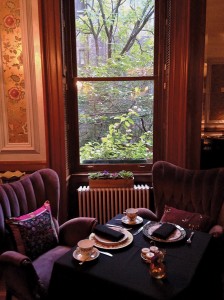

The next day, our Gilded Era weekend concluded with a lavish and leisurely afternoon tea at Lady Mendl’s, which is offered Wednesdays through Sundays at the inn (extremely popular, reservations are necessary). With four different tea pairings, the multi-course meal featured a seasonal soup and variety of sandwiches, as well as scones with clotted cream and an array of confectionaries.

Christine Donovan has written seven books about Hotel del Coronado’s history and is also author of Coronado, California: Hometown, Homeport, Home Away From Home.

With impeccable service and award-winning cuisine, Delmonico’s restaurant has been a New York landmark since the 19th century.