By: Christine Donovan

Editors note: The Vietnam War has been brought back into Americans’ consciousness with the 18-hour Ken Burns and Lynn Novick series on PBS. Upward of 500,000 servicemen and a few women were in Vietnam at one point, while behind them was an ever-changing political landscape and an increasingly conflicted America. Through it all, American prisoners of war, exemplified by Adm. James B. Stockdale, maintained a fierce loyalty to one another and love of country. Next February will mark the 45th anniversary of Stockdale’s release from Hoa Lo prison. The following is a portrait of the extraordinary strength of mind and will that fortified Stockdale and made him a remarkable leader under unfathomable circumstances.

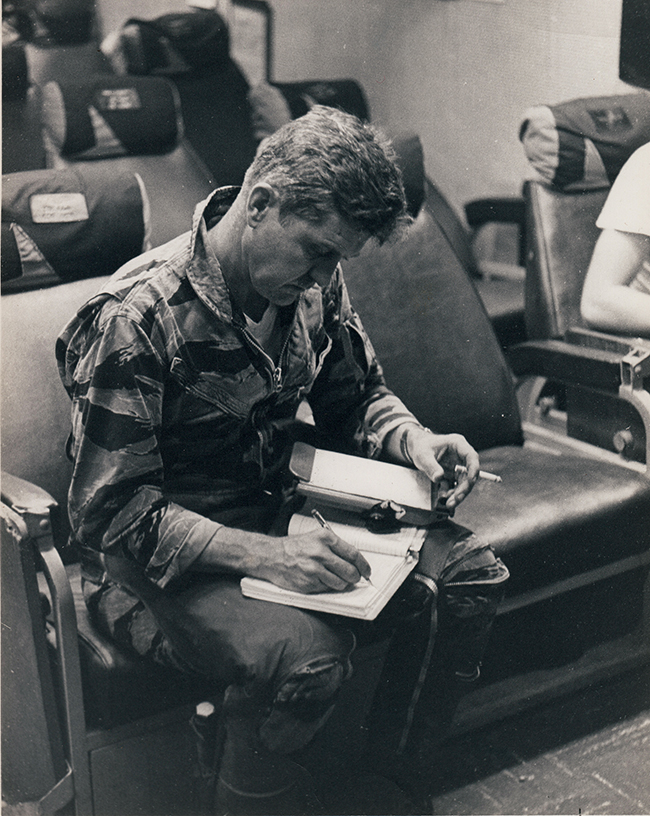

James Bond Stockdale, Coronado resident and Navy pilot, was shot down over North Vietnam on Sept. 9, 1965. Held as a prisoner of war (POW) in Hanoi’s Hoa Lo Prison (known at the “Hanoi Hilton”), Stockdale also spent more than a year in solitary confinement at an offsite “dungeon” facility with 10 other POWs. The self-described “Alcatraz Gang” had been exiled by the North Vietnamese because they had so effectively orchestrated prisoner resistance in Hoa Lo. At war’s end, when Stockdale was released in 1973, he was one of the highest-ranking and longest-held POWs. February 2018 will mark the 45th anniversary of the release of the admiral, who died on July 5, 2005.

At the time of his capture, Stockdale was 41 years old and, in his own words, “on top:” a wing commander aboard the aircraft carrier USS Oriskany, overseeing 1,000 pilots, crewmen and maintenance men. Stockdale’s wife, Sybil, meanwhile, was home on A Avenue, taking care of their four sons, ages 14, 11, 5, and 3. Already active in Coronado life, Sybil eventually took to the national and world stage, stepping forward as an outspoken and effective advocate for American prisoners of war.

While Stockdale was bravely leading a covert prison resistance in North Vietnam, enduring unimaginable torture and many stretches of solitary confinement, Sybil Stockdale was spearheading a humanitarian and later political effort, advocating for better treatment of Vietnam POWs, along with more accountability and improved communication (North Vietnamese did not abide by the Geneva Convention, which stipulated that POWs be identified, be allowed to correspond regularly with their families and be treated humanely.)

Neither spouse was fully aware of the other’s efforts. Stockdale had no knowledge of his wife’s national and international accomplishments (although his captors did) and Sybil Stockdale only assumed that her husband, as the senior Navy POW, was abiding by the “Code of Conduct,” which dictated that he “take command” and assume a leadership role, just as he had aboard ship.

In addition, the Pentagon asked Sybil Stockdale to include its coded messages in her letters to her husband. The government provided the encoding, so she didn’t know the contents. Stockdale, in turn, conveyed information to naval intelligence in his encoded letters home. Again, Sybil Stockdale wasn’t privy to the code, but she was well aware that her covert communication put Stockdale at added risk. (Thankfully, the North Vietnamese never uncovered the code.) The Stockdales wrote about their parallel experiences in the 1984 book, “In Love and War.”

Stockdale and stoicism

Stockdale was a singular war hero with a rare combination of abilities: A skilled and innovative fighter pilot, he earned the admiration and affection of his fellow flyers and the confidence and respect of his superiors. Beyond that, Stockdale had become a student of philosophy after studying the subject at Stanford University while earning a 1962 master’s degree in international relations.

Stockdale embraced the teachings of Epictetus, a first/second-century Greek scholar in the stoic tradition. Epictetus’ philosophy is preserved in the book, “The Enchiridion,” a copy of which Stockdale kept in his stateroom on the USS Oriskany. After he was captured, Stockdale was guided by Epictetus’ teachings having committed many to memory, calling the philosopher “my patron saint … my polestar.” He credits Epictetus with helping him survive — and even flourish — during his POW years. Stockdale often refers to the philosopher in his two books of essays published in 1984 and 1995: “A Vietnam Experience: Ten Years of Reflection” and “Thoughts of a Philosophical Fighter Pilot” (the essay, “Courage under Fire: Testing Epictetus’s Doctrines in a Laboratory of Human Behavior,” is also published as a stand-alone booklet).

Epictetus’ foundational principles (bolded below from “The Enchiridion”) were Stockdale’s constant companions during his captivity:

“For this is your duty: to act well the part that is given to you.” First and foremost, Stockdale accepted the fact that he was a POW, and he wasted no time bemoaning his fate. In fact, Stockdale remembered thinking, as he parachuted from his crashing plane into North Vietnam, “I’m entering the world of Epictetus” (all quotes taken from “Thoughts of a Philosophical Fighter Pilot,” unless otherwise noted). Stockdale was horribly beaten and crippled by North Vietnamese townspeople in the aftermath of the crash. As soon as his physical condition improved and as soon as prison circumstances allowed (he was often housed in isolated areas that prevented prisoner-to-prisoner communication), Stockdale went to work setting up a covert chain of command, with two over-arching directives. First, communication via a tapping code on cell walls was expected of all POWs. This was key to a unified resistance, even though prisoners would be tortured if caught in the act. Second, POWs were expected to resist being exploited for North Vietnamese propaganda efforts (although this, too, usually meant torture).

Even given the limitations imposed upon him, Stockdale concentrated his efforts on being the best commanding officer possible. Often in solitary confinement and frequently blindfolded, Stockdale had only actually seen a handful of the men in his command (which increased from about 75 POWs in the early days to almost 500 by war’s end), yet he took control where he could, crafting a mission-driven prisoner resistance that effectively thwarted North Vietnamese objectives again and again. Authoring the principle “Unity over Self,” Stockdale fostered a culture of camaraderie, where prisoners routinely put themselves in harm’s way in order to spare their fellow POWs, most of whom they had never met. Stockdale’s guiding principle — his “highest value” — was: “You are your brother’s keeper.”

After the POWs were released, Stockdale’s fellow prisoners heaped praise on him for his courageous leadership and for the example he set. Identified by the North Vietnamese as the architect of the resistance, Stockdale willingly took the brunt of torture and isolation. As Stockdale related in “In Love and War,” “We were not [in Hoa Lo] to cope, or languish, or sit out the war, or ‘be reasonable.’ We had learned to be very effective at making trouble for our adversaries, and at taking care of our own. And we loved it. It made life make sense to us.” As a result, Stockdale never regretted his years in prison, calling them “my most productive years on this planet,” for which he was awarded the Medal of Honor on March 4, 1976 by President Ford for his “heroic action … valiant leadership … and extraordinary courage.”

“Of things, some are in our power, and others are not.” Thanks to Epictetus, Stockdale understood that his thoughts were his own — beyond the reach of his captors. Although he suffered bouts of hopeless despair, Stockdale was always able to recapture his mental fortitude. This intellectual resilience — shared by other POWs — was life saving and is at the heart of stoicism: The ability to alter one’s attitude despite life’s circumstances. Although the word “stoic” has more recently become synonymous with a person who doesn’t show feelings or doesn’t have feelings, this modern-day interpretation is inconsistent with classic stoicism and would not have served Stockdale as a POW. Instead, inspired by Epictetus, who had also been crippled and held captive, Stockdale believed, “… there can be no such thing as being the ‘victim’ of another. You can only be a ‘victim’ of yourself. It’s all about how you discipline your mind.”

Most importantly, Stockdale honed the moral courage that Epictetus held in high regard, which Stockdale defined as “moral integrity under challenge.” Stockdale took to heart Epictetus’ admonition that physical injury was inconsequential compared to the injurious effect of destroying the moral man within: “Look not for any greater harm than this: destroying the trustworthy, self-respecting, well-behaved man within you.” Inspired by Epictetus, Stockdale held fast to his leadership goals despite the torture inflicted upon him. Not only did this help protect and inspire the men in his command, this provided Stockdale the inner reward the ancient philosopher had promised: “Tranquility, Fearlessness, and Freedom.”

“No man is free who is not master of himself.” For physical mastery, Stockdale, with a painfully compromised leg and often in leg irons, walked his cramped cell when he could to build up endurance. He also did daily push-ups whenever he was able (his arm was also compromised). Stockdale and many of his fellow POWs — who were denied basic medical care, underfed to the point of starvation and brutally tortured (some were tortured to death) — did everything they could to keep their bodies strong, to retain self-mastery.

Solitary confinement, as post-Vietnam War studies showed, was even more debilitating than torture, but POWs (most of whom were pilots, with a good deal of education) were unusually resourceful in combating isolation. Even when denied opportunities to communicate with each other, they kept themselves intellectually challenged. During one period of extended solitary confinement, Stockdale was able to mentally reconstruct a slide rule, scratching complicated formulae in the dirt and committing the results to memory.

Stockdale’s stoicism today

Stockdale’s philosophical essays continue to influence contemporary stoic scholarship, which contains many references to Stockdale’s life and his writing.

In addition, nearly every book about Vietnam POWs offers tributes to Stockdale’s unparalleled heroism, integrity and devotion to duty. There are also leadership theories drawn from his POW model, including the “Stockdale Paradox,” a concept author Jim Collins introduced in 2001, later paraphrased in the 2012 book, “Leading with Honor: Leadership Lessons from the Hanoi Hilton,” by Lee Ellis. It stated, “You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end — which you can never afford to lose — with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.”

The 2013 book, “Lessons from the Hanoi Hilton: Six Characteristics of High-Performance Teams,” by Peter Fretwell et al, with a foreword by Stockdale’s son James B. Stockdale II, is largely based on Stockdale’s inspired and inspiring leadership and the men in his command.

For additional information on Stockdale, visit the Stockdale Center for Ethical Leadership at usna.edu.

Christine Donovan, a Coronado historian, is author of “Coronado, California: Hometown, Homeport, Home Away From Home,” available at Bay Books, the Coronado Historical Association, Hotel del Coronado, and Amazon.

The Coronado Chamber of Commerce’s 2018 Salute to the Military will pay tribute to the American POWs held in Vietnam on the 45th anniversary year of their release. The military ball will be held on April 21, 2018 at Hotel del Coronado; for ticket information call (619) 435-9260.

Lessons of father remembered

by Stockdale’s sons

Raised in a family where “reading time” was routine, James and Sybil Stockdale’s eldest son, Jim (James Bond Stockdale II), recalls growing up in a house filled with books, many of which were history and philosophy. Beginning in adolescence, son Jim borrowed extensively from his parents’ library, but his father held back his copy of “The Enchiridion” (“I suspect it was in Dad’s bedside table,” he said). The senior Stockdale only introduced it to his namesake after he was released from Hoa Lo prison in 1973, when Jim was nearly 22 years old.

As Jim remembers, “Dad didn’t try to pitch or otherwise promote, or even talk about, stoicism until later … he seemed reluctant about touting it.” This reluctance was in keeping with Stockdale’s years as a POW, as he later explained: “Did I preach these things in prison? Certainly not. You soon learned that if the guy next door was doing okay, that meant that he had all his philosophical ducks lined up in his own way … no, I never mentioned stoicism once.” According to son Jim, “The lessons from Epictetus were deeply personal to Dad. He would use and apply stoicism to situations, but he was not inclined to bring up something publicly that was so precious to him.”

Second-born son Sidney, who was 11 years old when his father was captured, reconnected with his father as a college freshman. Sidney remembers their reunion: “This was when I first got to know my Dad, and our conversations made me aware of how intense his passion was for the experience of the man in battle on a philosophical level.” In their private time together, the senior Stockdale shared insights about stoicism, but always in an indirect way. Says Sidney, “It’s important to know that Dad never lectured anyone; he was much more inclined to tell a story … which revealed his understanding of human nature, and then perhaps in conversation he would say, ‘That’s where Epictetus had it right.’”

Youngest son Taylor, who was only 10 years old when his dad returned (“needless to say, we didn’t begin our relationship discussing stoicism”), characterized his father as a “deeply philosophical man, continually putting his life in perspective and doing the same for me as well.” Taylor recalls when he and Stanford, the second youngest son who died in 2014, learned from their mother that their dad’s lame leg could not be repaired. Says Taylor, “I remember being so scared walking up the stairs to greet him, wondering what his state of mind would be. My father was so brave and so gentle, saying, ‘Well, it looks like my sport will be swimming, are you good with that?’ Stan and I both nodded yes, and we hugged.”

It was during Stockdale’s last tour of duty at the U.S. Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island, that he included Epictetus in a course he co-created and taught in 1978-79, “Foundations of Moral Obligation.” This class soon became known as “The Stockdale Course” and produced a textbook by Stockdale’s co-creator and co-teacher Joseph Gerard Brennan. “Foundations of Moral Obligation: The Stockdale Course” is available on Amazon. Stockdale quotes Epictetus in the book’s foreword, “Let your study be how to suffer death, bondage, the rack, exile … difficulties are what show men’s characters,” but Stockdale tempered it with his own hard-earned insights, adding: “Nowhere does education of this sort give one more comfort than when called into the lair of one’s interrogator — or into the corridors of power.” Son Jim recalls that his father looked forward to introducing younger officers to the lessons of stoicism as a tool that could guide their decision-making in combat and morally ambiguous military situations.

Perhaps Stockdale’s most poignant legacy is borne by the USS Stockdale, an Arleigh Burke-class destroyer, commissioned in 2009 and homeported in San Diego. A few years ago, its commanding officer told Taylor that “ships take on their own distinct personalities, and the USS Stockdale had an attitude of resiliency and toughness.” A subsequent commanding officer told Taylor of the time the crew, disappointed that their deployment had been extended by a month, “started rallying as they challenged each other, ‘What would Adm. Stockdale do?’” Says Taylor, “I think my father’s philosophical legacy lives on in the lives of younger generations, which would mean more to him than anything else.”

![]()